| AVR Libc Home Page |  |

AVR Libc Development Pages | |||

| Main Page | User Manual | Library Reference | FAQ | Alphabetical Index | Example Projects |

| AVR Libc Home Page |  |

AVR Libc Development Pages | |||

| Main Page | User Manual | Library Reference | FAQ | Alphabetical Index | Example Projects |

Many of the devices that are possible targets of avr-libc have a minimal amount of RAM. The smallest parts supported by the C environment come with 128 bytes of RAM. This needs to be shared between initialized and uninitialized variables (sections .data and .bss), the dynamic memory allocator, and the stack that is used for calling subroutines and storing local (automatic) variables.

Also, unlike larger architectures, there is no hardware-supported memory management which could help in separating the mentioned RAM regions from being overwritten by each other.

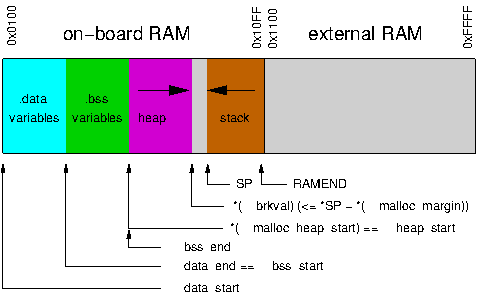

The standard RAM layout is to place .data variables first, from the beginning of the internal RAM, followed by .bss. The stack is started from the top of internal RAM, growing downwards. The so-called "heap" available for the dynamic memory allocator will be placed beyond the end of .bss. Thus, there's no risk that dynamic memory will ever collide with the RAM variables (unless there were bugs in the implementation of the allocator). There is still a risk that the heap and stack could collide if there are large requirements for either dynamic memory or stack space. The former can even happen if the allocations aren't all that large but dynamic memory allocations get fragmented over time such that new requests don't quite fit into the "holes" of previously freed regions. Large stack space requirements can arise in a C function containing large and/or numerous local variables or when recursively calling function.

On a simple device like a microcontroller it is a challenge to implement a dynamic memory allocator that is simple enough so the code size requirements will remain low, yet powerful enough to avoid unnecessary memory fragmentation and to get it all done with reasonably few CPU cycles. Microcontrollers are often low on space and also run at much lower speeds than the typical PC these days.

The memory allocator implemented in avr-libc tries to cope with all of these constraints, and offers some tuning options that can be used if there are more resources available than in the default configuration.

Obviously, the constraints are much harder to satisfy in the default configuration where only internal RAM is available. Extreme care must be taken to avoid a stack-heap collision, both by making sure functions aren't nesting too deeply, and don't require too much stack space for local variables, as well as by being cautious with allocating too much dynamic memory.

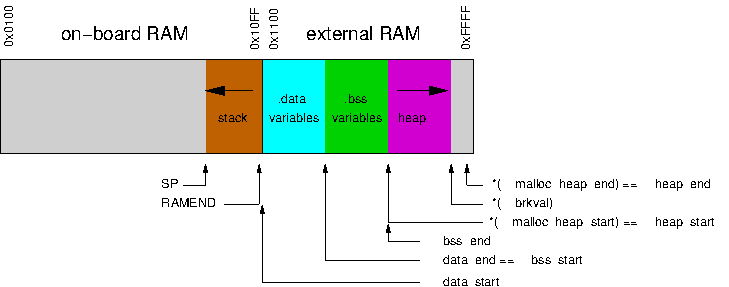

If external RAM is available, it is strongly recommended to move the heap into the external RAM, regardless of whether or not the variables from the .data and .bss sections are also going to be located there. The stack should always be kept in internal RAM. Some devices even require this, and in general, internal RAM can be accessed faster since no extra wait states are required. When using dynamic memory allocation and stack and heap are separated in distinct memory areas, this is the safest way to avoid a stack-heap collision.

There are a number of variables that can be tuned to adapt the behavior of malloc() to the expected requirements and constraints of the application. Any changes to these tunables should be made before the very first call to malloc(). Note that some library functions might also use dynamic memory (notably those from the <stdio.h>: Standard IO facilities), so make sure the changes will be done early enough in the startup sequence.

The variables __malloc_heap_start and __malloc_heap_end can be used to restrict the malloc() function to a certain memory region. These variables are statically initialized to point to __heap_start and __heap_end, respectively, where __heap_start is filled in by the linker to point just beyond .bss, and __heap_end is set to 0 which makes malloc() assume the heap is below the stack.

If the heap is going to be moved to external RAM, __malloc_heap_end must be adjusted accordingly. This can either be done at run-time, by writing directly to this variable, or it can be done automatically at link-time, by adjusting the value of the symbol __heap_end.

The following example shows a linker command to relocate the entire .data and .bss segments, and the heap to location 0x1100 in external RAM. The heap will extend up to address 0xffff.

-Wl options.

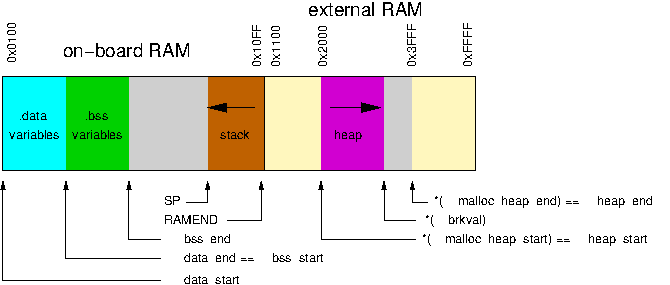

If dynamic memory should be placed in external RAM, while keeping the variables in internal RAM, something like the following could be used. Note that for demonstration purposes, the assignment of the various regions has not been made adjacent in this example, so there are "holes" below and above the heap in external RAM that remain completely unaccessible by regular variables or dynamic memory allocations (shown in light bisque color in the picture below).

If __malloc_heap_end is 0, the allocator attempts to detect the bottom of stack in order to prevent a stack-heap collision when extending the actual size of the heap to gain more space for dynamic memory. It will not try to go beyond the current stack limit, decreased by __malloc_margin bytes. Thus, all possible stack frames of interrupt routines that could interrupt the current function, plus all further nested function calls must not require more stack space, or they will risk colliding with the data segment.

The default value of __malloc_margin is set to 32.

Dynamic memory allocation requests will be returned with a two-byte header prepended that records the size of the allocation. This is later used by free(). The returned address points just beyond that header. Thus, if the application accidentally writes before the returned memory region, the internal consistency of the memory allocator is compromised.

The implementation maintains a simple freelist that accounts for memory blocks that have been returned in previous calls to free(). Note that all of this memory is considered to be successfully added to the heap already, so no further checks against stack-heap collisions are done when recycling memory from the freelist.

The freelist itself is not maintained as a separate data structure, but rather by modifying the contents of the freed memory to contain pointers chaining the pieces together. That way, no additional memory is reqired to maintain this list except for a variable that keeps track of the lowest memory segment available for reallocation. Since both, a chain pointer and the size of the chunk need to be recorded in each chunk, the minimum chunk size on the freelist is four bytes.

When allocating memory, first the freelist is walked to see if it could satisfy the request. If there's a chunk available on the freelist that will fit the request exactly, it will be taken, disconnected from the freelist, and returned to the caller. If no exact match could be found, the closest match that would just satisfy the request will be used. The chunk will normally be split up into one to be returned to the caller, and another (smaller) one that will remain on the freelist. In case this chunk was only up to two bytes larger than the request, the request will simply be altered internally to also account for these additional bytes since no separate freelist entry could be split off in that case.

If nothing could be found on the freelist, heap extension is attempted. This is where __malloc_margin will be considered if the heap is operating below the stack, or where __malloc_heap_end will be verified otherwise.

If the remaining memory is insufficient to satisfy the request, NULL will eventually be returned to the caller.

When calling free(), a new freelist entry will be prepared. An attempt is then made to aggregate the new entry with possible adjacent entries, yielding a single larger entry available for further allocations. That way, the potential for heap fragmentation is hopefully reduced. When deallocating the topmost chunk of memory, the size of the heap is reduced.

A call to realloc() first determines whether the operation is about to grow or shrink the current allocation. When shrinking, the case is easy: the existing chunk is split, and the tail of the region that is no longer to be used is passed to the standard free() function for insertion into the freelist. Checks are first made whether the tail chunk is large enough to hold a chunk of its own at all, otherwise realloc() will simply do nothing, and return the original region.

When growing the region, it is first checked whether the existing allocation can be extended in-place. If so, this is done, and the original pointer is returned without copying any data contents. As a side-effect, this check will also record the size of the largest chunk on the freelist.

If the region cannot be extended in-place, but the old chunk is at the top of heap, and the above freelist walk did not reveal a large enough chunk on the freelist to satisfy the new request, an attempt is made to quickly extend this topmost chunk (and thus the heap), so no need arises to copy over the existing data. If there's no more space available in the heap (same check is done as in malloc()), the entire request will fail.

Otherwise, malloc() will be called with the new request size, the existing data will be copied over, and free() will be called on the old region.